Micro-RCTs Meet Action Research: A New Model for Participatory School Reform in the North East

Last week, our co-founder Dr Wayne Harrison joined theDurham County Council–Durham UniversityEducation Working Group to share insights from our research collaboration with the North East Combined Authority, where we’ve been exploring how local research evidence generated by teacher-led micro-RCTs can inform school improvement. The study has taken us through a fascinating journey: from speaking with teachers about what’s working in their classrooms, to testing promising ideas through small-scale trials (micro-RCTs), to analysing how interventions are taken up in practice, and bringing teachers and policymakers together to decide what should be tested next through a Delphi process.

This led the team at WhatWorked Education to reflect not only on the outcomes from this project, but on the process - on how we got here, and what kind of research mindset sits behind this work. This kind of reflection is important for all researchers, but perhaps especially so in education where we still frequently see discussion around the so-called methods or paradigm wars. We find that we’re often asked to choose sides: randomised trials or case studies? Numbers or narratives? “Gold standard” or “just anecdote”? The problem with this framing is not just that it is false, it’s that it’s deeply unhelpful.

At WhatWorked Education, we believe these approaches are complementary, not contradictory. One informs the other. Qualitative research provides rich contextual insight and helps frame useful questions; experimental designs test them; practitioner feedback refines them. This creates a kind of reciprocal feedback loop where evidence evolves from practice and improves with it. That perspective led us to look more closely at how our work aligns with a tradition we’ve long admired: participatory action research (PAR).

What is Participatory Action Research?

PAR is more than a method. As Will Allen puts it in his brilliant piece inLearning for Sustainability, it’s also a mindset: a way of seeing change as co-created, iterative, and grounded in lived experience. PAR doesn’t just study communities; it works with them. It invites people to reflect on what they’re doing, how they’re doing it, and, crucially, why.

At its heart are four principles:

- Collaboration – People shape the research, not just participate in it

- Knowledge for action – Research is rooted in real-world challenges

- Social change – It tackles underlying causes, not just symptoms

- Empowerment – It builds the capacity for people to act on their own terms

These principles deeply resonate with our approach in the North East. Too often, teachers are excluded from research designed to improve their practice, even though they are the ones who know their pupils best. Our model puts them at the centre: identifying what’s working, testing it in their own classrooms, and contributing to the decisions about what should happen next.

PAR and Our School Improvement Model: Shared Foundations

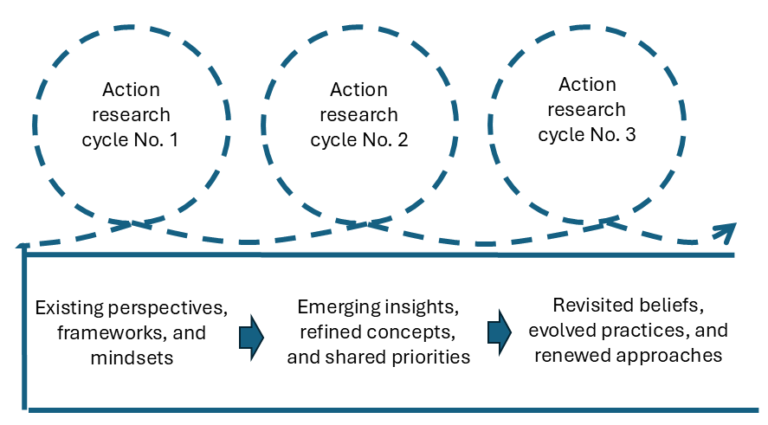

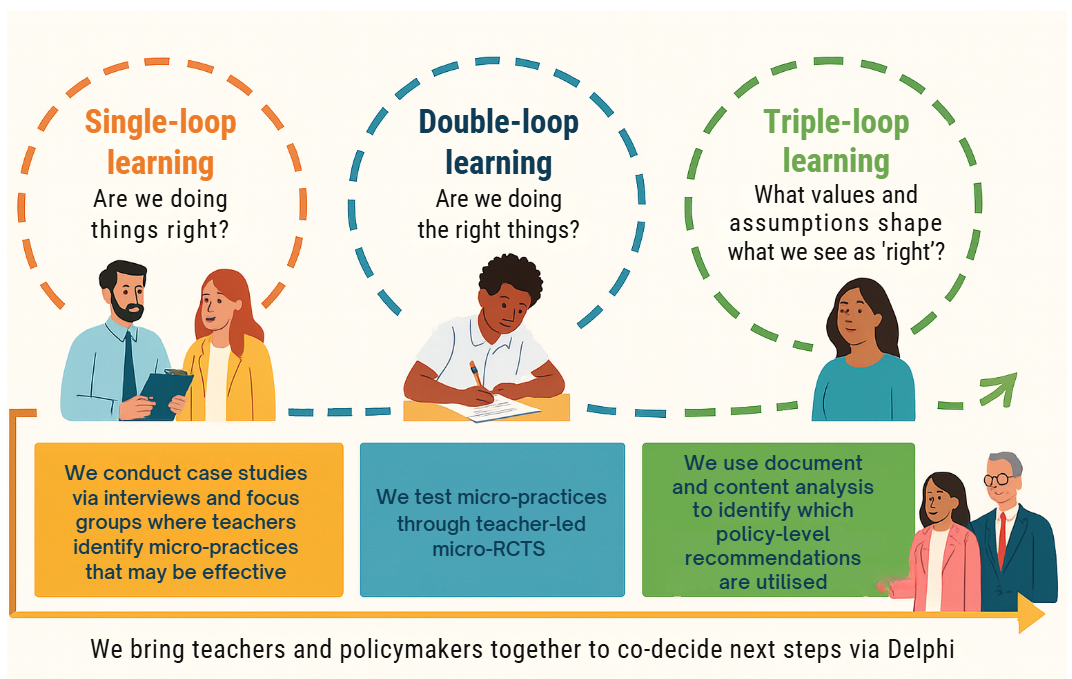

What struck us most about Allen’s framing of participatory action research, especially in tackling complex challenges, was its emphasis on cycles of learning:

🔁Single-loop learning:“Are we doing things right?”

🔁🔁Double-loop learning:“Are we doing the right things?”

🔁🔁🔁Triple-loop learning:“What values and assumptions shape what we see as ‘right’?”

This mirrors our own process:

- Teachers identify effective micro-practices via case studies →

- We test this through micro-RCTs →

- We analyse which policy-level recommendations get used and adapted →

- We bring teachers and policymakers together to co-decide next steps via Delphi

It’s iterative, reflective, built on real-time feedback, and most importantly, it recognises that knowledge is contextual and collective, not something handed down from outside, but developed by those inside the system.

Beyond the Classroom: Evidence That Spans Micro, Meso and Macro Levels

While our approach draws heavily on the principles of participatory action research, particularly its commitment to collaboration, reflection, and real-world relevance, it also seeks to generate evidence that operates across different levels of the education system.

At the micro level, we work directly with teachers to trial interventions in their own classrooms. These micro-RCTs are small-scale by design, giving teachers autonomy to test what matters most to their pupils and providing rapid, actionable feedback.

At the meso level, we use cumulative meta-analysis by aggregating the results from individual teacher trials to help us understand patterns of adaptation and sustainability - not just whether something worked once, but how and why it might work again elsewhere.

At the macro level, we conduct content analysis of Pupil Premium strategies and engage policymakers and school leaders through a Delphi process to identify utilisation of and co-prioritise interventions that show promise and relevance. This ensures that system-wide decisions are grounded in both teacher-generated evidence and collective professional judgement.

By deliberately connecting these layers, our model creates a kind of vertical coherence. It respects the lived experience of practitioners, builds cumulative insight across schools, and supports strategic decisions at a policy level. In doing so, it addresses one of the key critiques of traditional research models: that they often fail to link classroom practice with system-wide change.

Who Needs to Be In the Room?

This kind of vertical coherence, linking classroom insight to system-level strategy, can only happen when we bring the right people into the process from the start. It’s not just about levels of evidence, but layers of voice and experience. This is something that really resonates with our work. In a recent LinkedIn post, Marc Harris, Head of Insight and Impact at NHS Horizons asked: Who needs to be in the conversation if we want real change?He shared a visual by Bill Bannear that captures it perfectly: it sets out four key voices essential for meaningful, lasting change.

- Voice of Intent- those with passion and mandate

- Voice of Experience- those who live the issue

- Voice of Design- connectors, facilitators, documenters

- Voice of Capability- those with tools, access, resources

The challenge and opportunity is to bridge these voices, deliberately and thoughtfully. This is exactly what we’re trying to do in the North East: bring together teachers (experience), policymakers (mandate), researchers (design), and local systems (capability) to shape a shared improvement agenda. Our platform enables teachers to generate their own data, not just respond to someone else’s. Our Delphi approach helps translate that data into region-wide priorities. And by combining the rigour of trials with the reflexivity of dialogue, we hope to show that it is possible to build an evidence ecosystem that is both rigorous and rooted in the context of the region we are hoping to support.

Beyond Education: A Model with Broader Potential

While our focus has been on school improvement in the North East, the principles behind this approach, blending participatory action research with iterative experimentation, are by no means limited to education. In fact, this model could be applied across a wide range of disciplines where systems are complex, change is context-dependent, and real-world solutions need to be both grounded and scalable.

Sectors like public health, social care, youth services, and environmental planning all face similar challenges: how to bridge the gap between lived experience and policy decision-making; how to move beyond top-down interventions toward co-created, adaptive change; and how to generate contextualised evidence that is both credible and actionable.

The strength of this approach lies in its flexibility. It invites practitioners into the research process, uses feedback loops to refine interventions, and connects micro-level insight to macro-level decision-making. Whether you're developing a new community wellbeing strategy or testing approaches to increase youth engagement, this method helps answer not just what works, but for whom, in what context, and why. It is, in many ways, a methodology for adaptive systems leadership - an approach that honours expertise in all its forms and recognises that the most sustainable change happens when people shape the solutions they live with. We’ve started in education, but we firmly believe this way of working could inform cross-sector innovation and help build more inclusive, grounded and evidence-informed public services.

In Conclusion: Complementarity, Not Competition

As Allen writes, “Participatory action research brings depth, responsiveness, and relational insight - what’s often missing in conventional evaluation or impact assessments.” Here at WhatWorked Education we don’t believe we need to choose between methods. We believe we need to choose relationships, relevance, and respect. Our work in the North East is a reminder that the real question isn’t “Which method is best?” but rather, “Which approach best meets the needs of the people we're aiming to support?”. If we want school improvement that works, we need to build it with the people who live it every day.

Copyright © 2025